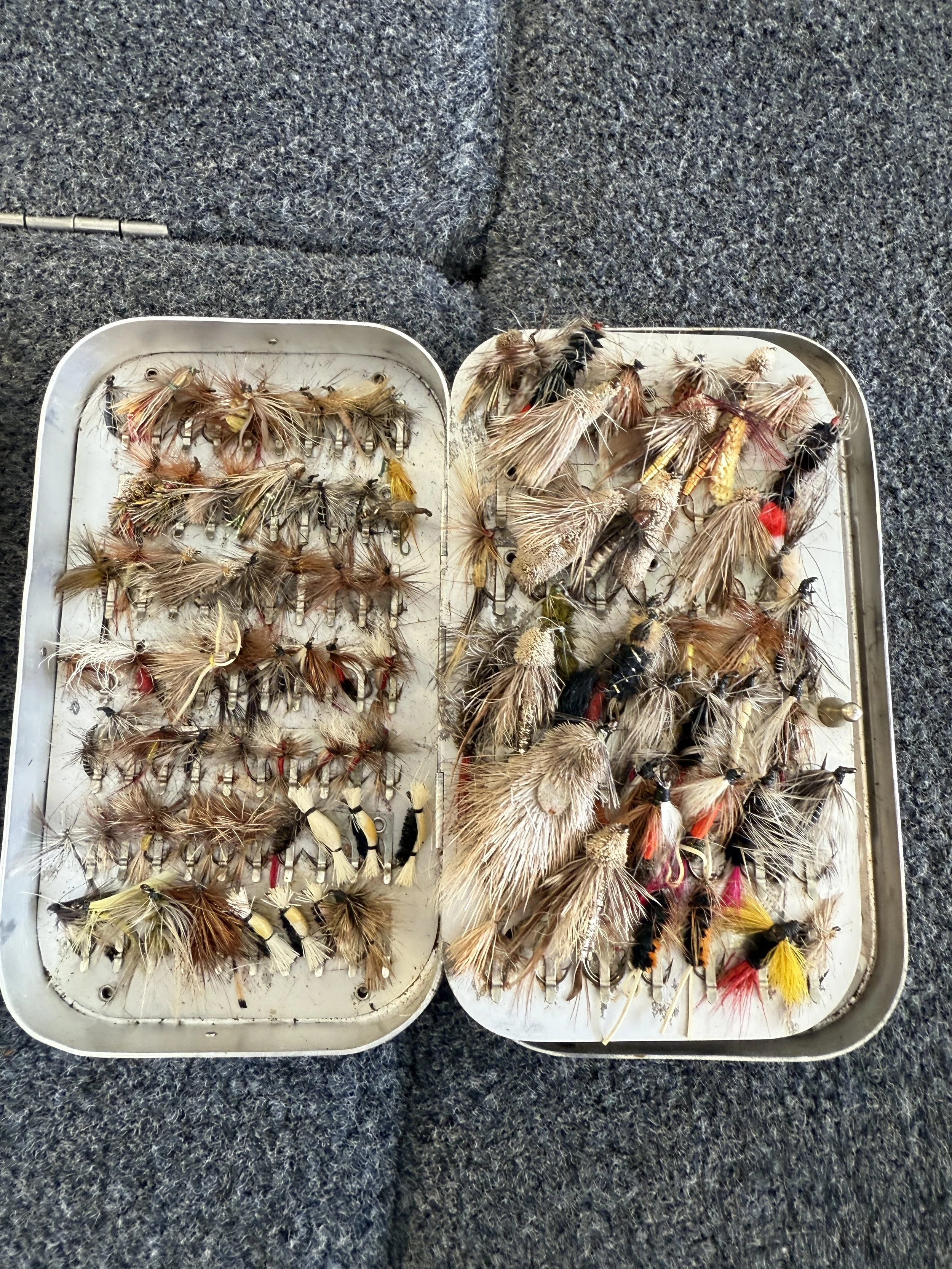

That following weekend, he took me down to Balboa Park. Under the dappled shade of a massive oak tree in a small building, a council of wizards held their court. They were all men over fifty, with leathery skin, kind eyes, and glasses—bifocals and great, magnifying lenses clamped to their heads. They peered into their vices with the intensity of surgeons, their fingers, thick and calloused from a lifetime of work, performing miracles of delicacy.

They were tying flies. And they welcomed me, this wide-eyed eight-year-old, into their circle.

They taught me the ancient dances of thread and feather: the whip finish, the half-hitch, how to palmer a hackle. They’d lean in, their magnifying glasses making their eyes look huge, struggling to thread a hook a size 22 midge. Meanwhile, my young eyes, unaided, could see it all perfectly. I was their secret weapon. And of all the patterns they taught me—the Royal Wulffs, Matukas, the Woolly Buggers, Hornbergs—my favorite, my signature, was the simplest: the Hare's Ear Nymph. It was elegant, deadly, and it was mine.